Worksheet 11 - Hints and Selected Solution

1. For which sets A is it the case that the only bijection

from A to A is the identity?

Answer. For sets A consisting of exactly one element, as well as for the empty

set.

2. Let A be the set of the days of the week. Let f assign to each day of the

week the number of letters

in its name in English. Is f an injection?

Answer. No. f(Monday) = f(Sunday) but Monday ≠ Sunday.

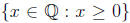

3. Let A be the set of subsets of  that have

even size, and let B be the set of subsets of

that have

even size, and let B be the set of subsets of

that have odd size. Establish a bijection

from A to B. (

that have odd size. Establish a bijection

from A to B. (![]() )

)

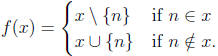

Proof. Let A be the collection of even-sized subsets of

, and let B be the collection of

, and let B be the collection of

odd-sized subsets. For each x ∈ A, define f(x) as follows:

By this definition, #(x) and #(f(x)) differ by one, so f(x)

is a set of odd size and f maps A into

B.

We claim first that f is one-to-one. Consider distinct x, y ∈ A. If both

contain or both omit n,

then f(x) and f(y) agree on whether they contain n but differ outside {n}. If

exactly one of {x, y }

contains n, then exactly one of {f(x), f(y)} contains n. Thus f(x) ≠ f(y), and f

is one-to-one.

We next claim that f is onto. If z ∈ B, then flipping whether n is present

in z yields a subset x

such that f(x) = z, so f is also onto, and hence f is a bijection.

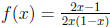

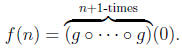

4. Verify that  defines a bijection from the

interval [0, 1] to R. (Hint: In the proof that

defines a bijection from the

interval [0, 1] to R. (Hint: In the proof that

f is surjective, use the quadratic formula.) ( )

)

Proof. f is injective Suppose that f(x) = f(y). Then we obtain that

(2x - 1)2y(1 - y) = (2y - 1)2x(1 - x),

which simplifies further to 2(y2 - x2) - 2(y - x) = 4xy(y - x). If y ≠ x, then

we can divide

by 2(y - x) to obtain y + x - 1 = 2xy. Rewriting this as -xy = (x - 1)(y - 1)

makes it clear

that there is no solution when x, y ∈[ 0, 1], since the left side is negative and

the right side is

positive. Therefore we conclude that x = y, and so f is injective.

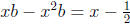

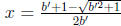

f is surjective Suppose that f(x) = b. We solve for

x to obtain x ∈[0, 1] such that f(x) = b.

Observe that b = 0 is achieved by  , so we may assume that b ≠ 0. Clearing fractions

, so we may assume that b ≠ 0. Clearing fractions

leads to  , or

, or

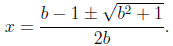

. The quadratic formula yields

. The quadratic formula yields

The magnitude of the square root is larger than lbl.

Therefore, choosing the negative sign in

the numerator yields a negative x, which is not in the domain of f. We therefore

choose the

positive sign.

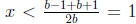

If b > 0, then the square root is less than b + 1, and we obtain

. Also, the

. Also, the

square root is bigger than 1, so x > 0. If b < 0, then let b' = -b. The formula

for x becomes

, where b' > 0. the square root is strictly between 1 and

b' + 1, so x is

strictly

, where b' > 0. the square root is strictly between 1 and

b' + 1, so x is

strictly

between 1/2 and 0. In each case, we have found x in the domain [0, 1] such that f(x) = b,

and

we have thus established that f is onto.

5. Let f and g be surjections from R to R, and let h = fg be their product. Must

h also be surjective?

Give a proof or a counterexample.

Counterexample. Let f, g : R → R be defined by f(x) = g(x) = x. Then both f and

g are

surjective, but (f · g)(x) = x2 is not surjective.

6. Determine which formulas below define surjections from

onto

onto  :

:

(a) f(a, b) = a + b.

Answer. Not surjective. (Why?)

(b) f(a, b) = ab.

Answer. Surjective. (Why?)

(c) f(a, b) = ab(b + 1)/2.

Answer. Surjective. (Why?)

(d) f(a, b) = (a + 1)b(b + 1)/2.

Answer. Not surjective. (Why?)

(e) f(a, b) = ab(a + b)/2.

Answer. Not surjective (Why?)

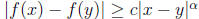

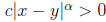

7. Given f : R → R, suppose that there are positive constants c, α such that

for all x, y ∈ R,

. Prove that f is injective.

. Prove that f is injective.

Proof. Suppose that f is not injective. Then there exist distinct numbers x and

y such that

f(x) = f(y). Since  , this contradicts the hypothesis.

, this contradicts the hypothesis.

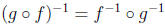

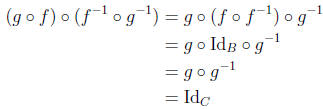

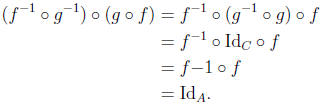

8. If f : A → B and g : B → C are bijections, prove that

.

.

Proof. We use exercise 11. Since f and g are bijections, both are invertible. Note that

and

9. Given f : A → B and g : B → C, let h = g o f. Determine

which of the following statements are

true. Give proofs for the true statements and counterexamples for the false

statements.

(a) If h is injective, then f is injective.

Answer. True. (Why?)

(b) If h is injective, then g is injective.

Answer. False. (Why?)

(c) If h is surjective, then f is surjective.

Proof. False. (Why?)

(d) If h is surjective, then g is surjective.

Proof. True. (Why?)

10. Consider f : A → B and g : B → A. Answer each question below by providing a

proof or a

counterexample.

(a) If f(g(y)) = y for all y ∈ B, does it follow that f is a bijection?

Proof. No. (Why?)

(b) If g(f(x)) = x for all x ∈ A, does it follow that f(g(y)) = y for all y ∈ B?

Proof. No. (Why?)

11. Consider f : A → B and g : B → A. Prove that if f o g and g o f are identity

functions, then f is

a bijection. In particular, prove that

(a) If f o g is the identity function on B, then f is surjective.

Proof. If y ∈ B then f(g(y)) = y. Hence there is an element of A mapped to y by

f, namely,

the element g(y). This shows that f satisfies the definition of a surjection.

b) If g o f is the identity function on A, then f is

injective.

Proof. If x ∈ A, we have that g(f(x)) = x. If f is not injective, then there

exist distinct

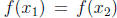

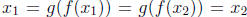

elements  ∈ A such that

∈ A such that

. If we apply g to both sides of the

equality,

. If we apply g to both sides of the

equality,

we obtain  , which contradicts our choice of

distinct elements.

, which contradicts our choice of

distinct elements.

Hence our assumption that f is not injective must be wrong.

12. Consider f : A → A. Prove that if f o f is injective, then f is injective.

Proof. Suppose that f(x) = f(y). Then f(f(x)) = f(f(y)). By the definition of

composition, this

yields (f o f)(x) = (f o f)(y). The hypothesis that f o f is injective yields

now that x = y. We

have proved that f(x) = f(y) implies x = y, and so f is injective.

13. Construct an explicit bijection from the closed interval [0, 1] onto the

open interval [0, 1]. (![]() )

)

Hint. This is a very nice problem. In short, no hint!

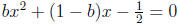

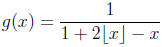

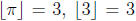

14. Consider the function g : R → R defined by

where for any x ∈ R, [x ] denotes the largest natural

number less than or equal to x. (For example,

, and

, and  .) Let f : N

→ Q be the function defined by

the following

.) Let f : N

→ Q be the function defined by

the following

rule:

Then prove that f is a bijection between N and

, where

, where  denotes the set

denotes the set

.

.

(At least convince yourself that this is true!)

(At least convince yourself that this is true!)

Remark. This last exercise should be a final project.